How Do We Change a Culture?

The million-dollar question doesn’t have a single answer, but there are tools and ideas that help us navigate it. This Substack is all about that. Welcome.

Culture as everything that, in the use of anything, reveals value beyond mere utility. Culture as that which, in each object we produce, transcends the merely technical. Culture as the powerhouse of a people’s symbols. Culture as the set of signs of each community and the entire nation. Culture as the meaning of our actions, the sum of our gestures, the sense of our ways. – Gilberto Gil

When we think about culture, many things come to mind: from practices to ideas, from habits to ways of thinking, from rituals and traditions to everyday life. Culture seems to be a vast umbrella that covers both the arts and their forms of expression (theater, cinema, literature, etc.) and entertainment activities (going to the cinema, dining out, gaming, etc.), as well as more general collective practices, like having animals as a centerpiece at main meals, performing rituals in sacred places, or simply eating bread, rather than rice, for breakfast.

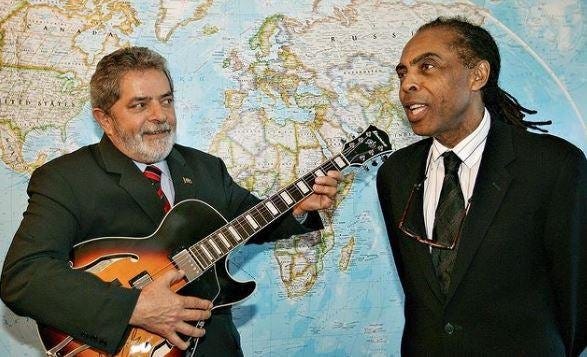

Almost everything fits under this common denominator called "culture." Culture can be extraordinary, as in artistic creations that open us to radical new ways of seeing the world, but it can also be ordinary, as the English cultural critic Raymond Williams noted in his 1958 essay Culture is Ordinary, critiquing the elitist notion of culture as something reserved only for the "educated" or wealthy in society. Or, as the Brazilian singer Gilberto Gil said while serving as Minister of Culture under Lula’s administration from 2003 to 2008, “Culture is like rice and beans; it’s a basic need.” He was referring to the common view within public policy priorities that culture should be merely the "icing on the cake" of the public budget, implying it doesn't address fundamental issues such as hunger.

I’ve found it helpful (though not necessarily accurate) to think of culture as "forms of life," a concept developed by the philosopher Rahel Jaeggi in her book Critique of Forms of Life. I say not necessarily “accurate” because, for Jaeggi, culture and history precede forms of life. But to avoid long philosophical debates — as here I’m less concerned with philosophical rigor and more with the usefulness of ideas to understand the world — I’ve been thinking of culture as forms of life, because what we do and think—our practices and ideas—are woven together in the fabric of a form of living. This concept inspired much of my doctoral thesis, titled Resentment and Mistrust in the Neoliberal Form of Life, soon to be published by PUC/Rio’s press. As I wrote in my thesis (and I’ll quote below to expand on it later):

Jaeggi defines forms of life by four specific points:

forms of life should not be understood as an issue of individual or collective practices but as a set of practices interconnected or interrelated in one way or another;

forms of life are collective formations, even if individuals participate in and relate to them as individuals. This means an individual's form of life refers to their participation in a collective practice;

forms of life contain both active and passive elements. While an individual lives within a pre-existing form of life, they also create and transform it through their own practices. Therefore, something that never changes and cannot be altered does not constitute a form of life;

as orders of social cooperation that rely on regular practices, forms of life are sustained by an implicit normativity.

Thus, as animal advocates, if we’re committed to ending animal exploitation through interventions we deem most appropriate to the context, our skills as individuals, or to make philanthropic investments more effective (or whatever our individual or organizational motives might be), it’s crucial we understand how what we aim to change actually functions.

The “culture” or “form of life” we aim to change:

is a set of interrelated practices that permit the consumption of animals on various fronts. Our action must be multi-strategic, with transformative goals across different spheres of social life. Supermarkets, laws, and products need to change. But so do religions, educational curricula, media narratives, culinary traditions, gender norms, and other social norms and spaces (or "pillars of support," as named by the Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies) so that animals are seen through lenses that recognize their inherent value, inner lives, and personal goals. To understand more about the multi-strategic nature of social movements, the Movement Ecology model, developed by the Ayni Institute, is quite helpful. I’ll talk about it on December 8 at the AVA Summit Latin America, a must-attend event that still has open registrations (check it out!). Furthermore, for an overview of the systemic and complex nature of animal exploitation, I highly recommend Rachel Mason's excellent report on the subject, which has a summary on this Faunalytics blog.

[the “culture” or “form of life” we aim to change] has a collective dimension that makes individual transformation efforts insufficient against the overwhelming force of the status quo. This doesn’t mean that individual change strategies aren’t important (far from it!). But while focusing on individual transformations, which are essential interventions in a healthy social movement ecosystem (as shown in the model developed by Ayni Institute), we must emphasize the collective nature of the problem. Animal issues shouldn’t be reduced to the call #govegan; they represent a structural problem that must be addressed as such. However, if you’re part of the social transformation movement for animals, adopting veganism is simply part of the journey if you’re a reasonably coherent human. In short, individual changes aren’t useless but insufficient; more is needed to change a form of life.

[the “culture” or “form of life” we aim to change] is inherently subjected to change. This may seem obvious to those in the movement, but who hasn’t felt defeated by the overwhelming power of the mainstream? Nonetheless, the possibility of transforming a form of life is real. Social change is the enabling condition for the existence of any social form, as social forms both shape and are shaped continuously. By adopting a practice differently within the context of a form of life, we are already transforming it. Refusing to sit at a table where a dead animal is being served, for instance, is a way to reframe a form of life’s practices and, in doing so, to transform them. The suggestion of the Liberation Pledge, while controversial and difficult in practice, has undeniable transformative potential. For more, I recommend Eva Hamer's enlightening article on the subject.

[the “culture” or “form of life” we aim to change] has an implicit normativity. In other words, it doesn’t legally prohibit veganism, but it excludes those who refuse to participate in the system through a punitive system that is not concrete but subtle. The punishment is expressed as a subtil form of social exclusion. Simultaneously, it also rewards those who adhere to the norm — and the reward is social inclusion. These norms aren’t written on paper, but we all know what they entail, what they talk about, who they reward, and who they exclude.

EMERGENT STRATEGIES

Finally, we must remember that social transformation emerges from within the fabric of society. It has never been the product of the creation by a group of clever technocrats, for example. For Rahel Jaeggi, a Hegelian par excellence, forms of life transform for reasons grounded in reality, emerging through the resolution of problematic situations or shifts in the perception of problems. Unlike the fashion world, for example, where powerful agents launch products and styles from their own creative efforts, changes in a form of life emerge from the heart of social life itself. In this sense, what drives societal change is society itself, not an external solution crafted by an elite with a ready-made fix. For example, the transformation of a rural, feudal family into a bourgeois nuclear family resulted from changes in socio-economic conditions and normative expectations in feudal societies. Forms of life change because something has shifted within a specific society.

In this context, regarding animals, any social change strategy focused only on technological solutions, like plant-based meats or futuristic cheeses, won’t fulfill the social transformation it promises. Just as individual changes are insufficient, so are technological ones. This is because we need multiple strategies, and we need society at large to engage in this massive social change project.

However, when it comes to thinking about the most effective interventions, I believe that interventions that expose the deep crisis of current societies and that promote solutions that, like a lotus flower, emerge from the very mud of the problem itself, have one of the greatest potential for social change. In a crisis, we all find the best way forward. Or, as the poet and singer Leonard Cohen, perhaps unknowingly a Hegelian, once said: “There is a crack in everything. That's how the light gets in.”

The topic may seem too academic, but I was fortunate to encounter, in my last two fulfilling years as a strategist at Animal Think Tank, various interesting models offering Hegelian-inspired solutions to the problem of social change. Aside from Movement Ecology, one of my favorites comes from the book Cultural Strategy by Douglas Holt and Douglas Cameron, about how ordinary brands became cultural icons like Patagonia, Ben and Jerry’s, and Marlboro: by seizing ideological opportunities that mainstream culture missed.

The idea behind this model is that cultural change emerges from the status quo itself, represented in the model as “cultural orthodoxy.” The model demonstrates that every mainstream has a fracture, and this flaw can be found in demands for a “better ideology,” represented in the model as “ideological opportunity.” These demands for a “better ideology” are tied to the broken promises of a form of life. I really suggest you reading this book to understand better the model. This article by Douglas Holt, published in Harvard Business Review, offers a good summary of the model.

I'm planning to publish a series of posts about this model, so I won't go into detail just yet. What’s important for now is to remember that brands that became iconic knew how to seize ideological opportunities to launch something society desired—not only explicitly, at the level of discourse, but also, and especially, in a more subtle and unconscious way, manifesting at the fringes of society itself.

After all, as Rahel Jaeggi explained, a form of life can be assessed—and, in certain respects, compared to others—based on its problem-solving strategies. We could say, therefore, that a form of life is either successful or failing depending on its ability to address the problems it claims to resolve. Social movements, subcultures, forms of resistance, mental health conditions, and collective deviant behaviours all indicate the breakdown of a form of life. At the same time, these signs offer insights into potential paths forward, pointing to emerging solutions that can take us from one place to another.

With this in mind, the questions I’m reflecting on are as follows:

How does the crisis of a society that exploits animals for consumption manifest?

How did animal exploitation come to be accepted as a problem-solving strategy (and what were those problems)?

What are our solutions to these issues?

What do subcultures, marginalized groups, mental health conditions, and social movements reveal about the failure of our form of life?

And, historically, when has what was once considered deviant become the path to the new?

And what are your thoughts on that? Share them below!

*

This is the first post of the bilingual Substack Baby Gaia, focused on cultural change for animals. If you have post suggestions, or would like to collaborate, suggest interviews, or share book recommendations, feel free to reach out to me at baiburil [at] gmail [dot] com. For the time being, welcome!